The next game I’m making is all about animal locomotion so I figured a good first step would be to improve my eye for motion. To do that I’ve spent the past year taking classes to become a better animator, creating shots like this:

Animation I did for a class on combat body mechanics

I’ve reached a point now where I’m starting to forget some of the things I’ve learned as they become habits that have been drilled into me, instead of conscious knowledge. I thought it might help reinforce and clarify what I’ve learned if I summarized the highlights here.

Animation theory

- Animation isn’t about motion, it’s about poses. Bringing a character to life comes from creating poses that express how they’re feeling. Motion is important but early on it’s a distraction from the real goal of evoking your character. Richard Lico, a former Lead Animator at Bungie, says he spends 70% of his time refining his core poses and 30% on everything else. He compares it to the classic Disney workflow where senior animators would draw the critical frames that told the story while an army of junior draftsmen drew the frames in between. Nowadays we’ve replaced the draftsmen with a computer.

- Animation is about art directing motion, not just making it believable. As an animator you’re not only making things move, you’re framing and adjusting motion to make it clearer and more expressive. For example, if a character drops his sword, shield and helmet when he dies then physics might say each of those objects should land at the same time but it’s easier for the audience to read and more visually appealing if each object lands on a different frame like they do here:

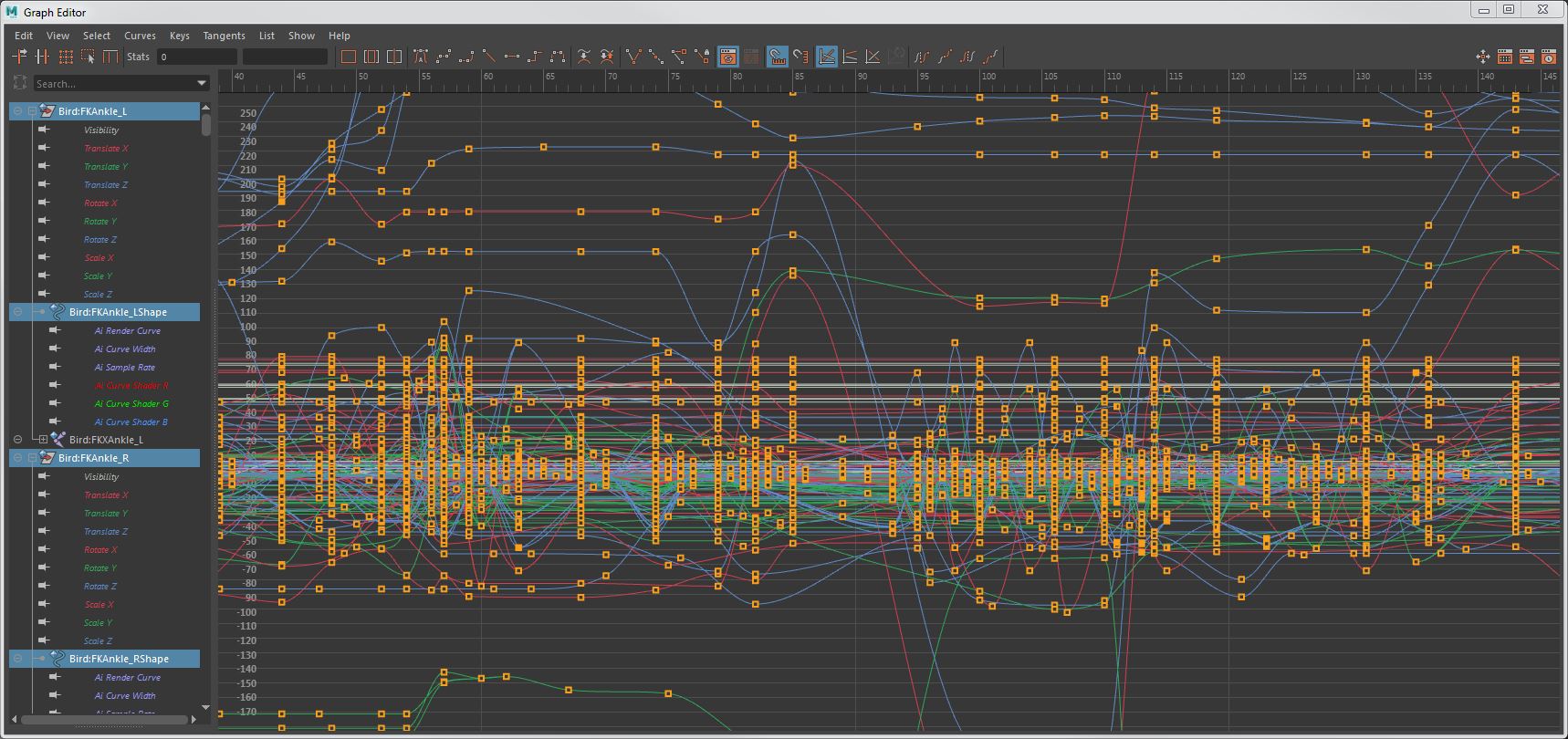

- Animation is a constant struggle not to get lost in the details. There’s so much to think about when animating that it’s easy for all your attention to get sucked into fixing whatever looks broken. You start seeing your character as a collection of problems or a mechanical puzzle to solve, rather than a living thing. For example, when animating a character running and then veering to the right I treated it like they were running straight ahead and then I gradually rotated their whole body like a ship. I forgot that living things tend to turn their head and look in the direction they’re going to turn before they start rotating the rest of their body. I was seeing the world from camera’s perspective, rather than seeing it through the character’s eyes and then trying to convey that experience. The hard part is that in order to ignore the technical aspects you have to immerse yourself so fully in the technical minutia that they become automatic and you can focus on what’s actually important. As an example, here’s what my animation curves looked like for the first shot I posted above:

This is the sort of thing you spend a lot of time looking at as an animator

The first two dimensions are the hardest

- Even when you’re animating in 3D most of what makes an animation look and feel good has to do with what happens in 2D.

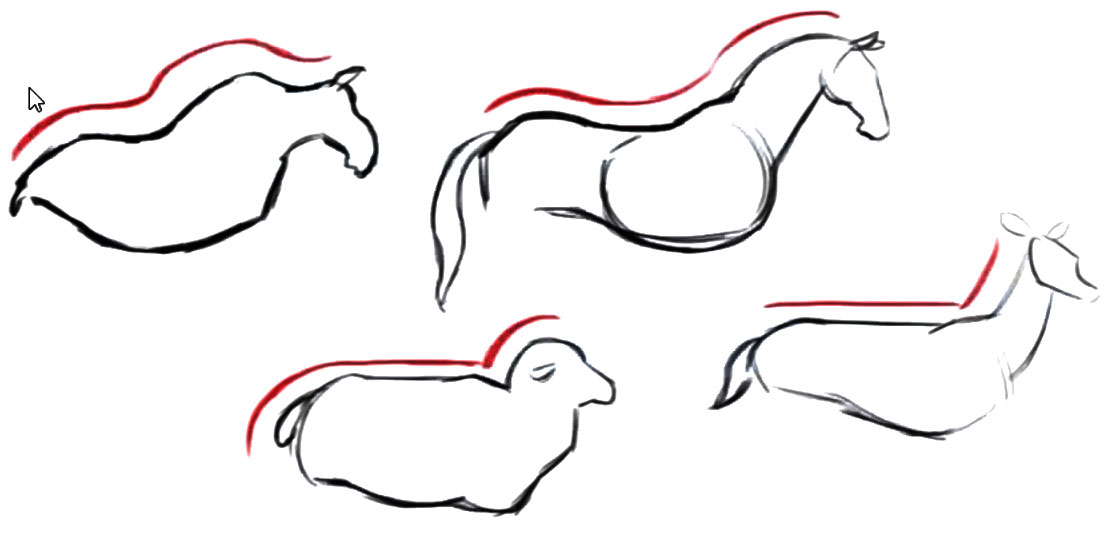

- The first thing people notice about your poses — and maybe the only thing — is the overall line of action. That’s a 2D phenomenon. To make a motion feel clear and powerful it helps to speak loudly and in visual terms we do that using fundamental shapes like a character going from a “Reverse C” to a “C” shape:

- Everything in a living organism should move in arcs and what those arcs look like are profoundly influenced by where the camera happens to be

- Clear silhouettes make motions easier to read and are created by reducing visual overlap between body parts and emphasizing negative space, very much 2D issues. In games this gets tricky because the player often controls where the camera is, though Richard Lico says that if you make your poses look good from the front and the side, most of the time it’ll hold up from any angle.

- Animation feels better when there’s MORE of it. Specifically, increasing the NUMBER of moving parts on a character makes them feel livelier and more appealing. The motions themselves can be pretty basic, just having enough details like ears flapping and bracelets bouncing somehow tricks us into believing this character is real. It reminds me of Walter Murch’s observation that we can distinguish two sets of footsteps but with three sets all we hear is a crowd. I think if a character’s motions are too simple then our brains can easily track everything, which is part of what makes it feel fake, but there’s a tipping point where suddenly too much is happening in the body for us to take it all in so we stop trying and just relate to it as a holistic organism.

Timing

- Avoid having things start or stop moving on the same key because it tends to look boring and unnatural. For example, when jumping it usually feels better if each foot leaves the ground on a different frame or for a jumping attack you wouldn’t want the character to land and have the weapon impact on the same frame. Spreading things out helps create rhythm and adds visual interest. Similarly when parts of the body settle, it’s more interesting to see the hips, chest and head all come to rest at slightly different times.

- Rhythm is important for individual actions AND for entire scenes. For our sanity, when working on longer scenes animators usually break them up into smaller beats and polish those one at a time. So if the scene is about a character pulling their pants on, grabbing breakfast out of a toaster and then running out the door, you’ll generally start by polishing the rhythm of each of the three actions so there’s a satisfying contrast of high and low intensity movement. But it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that you want each of those actions to have a different duration and intensity FROM EACH OTHER, otherwise the scene as a whole will feel monotonous, like tapping out “Shave and a Haircut” three times in a row.

- You need moments of stillness to give definition to the motion and make the whole feel readable and crisp. It’s tempting to keep the character moving but our brains and eyes need to rest sometimes so that what we’ve seen has a chance to sink in. It’s like having spaces between words.

Anticipation and showing impact

- Anticipation makes any motion feel better, especially large movements. I think it’s a combination of realism (bodies take awhile to get moving), the chance to draw the eye, and having a moment to rest which helps create contrast.

- To make a motion feel fast and powerful, delay the start and hold the ending. For really fast actions the motion and even the moment of impact aren’t that important. It’s counter-intuitive but makes sense if you think about the alternative of trying to get an axe to feel weightier by swinging it faster, which would just make it seem lighter and also harder to see. Adding time before and after the action calls attention to how fast the movement is, even if we can barely see it.

- For fast motion like a melee attack the clarity of the reaction is more important than the attack. The reaction tells us what happened even if the earlier movements were too fast to follow, answering questions like: “did the hit connect and how hard was it?”

- Changing where a character is looking is an easy way to create anticipation and also suggest their thought process.

- Although games usually avoid having anticipation for player actions (because they make controls feel sluggish), a few frames of anticipation feel OK as long as you immediately start moving the player in the direction of their action, eg an attack. It’ll feel responsive even if the action itself takes a few frames to connect with its target.

- In games, attacks often include a “hit frame” that pauses the moment of impact for a few frames. For example, in God of War when you swing your axe into an enemy it stops there for several frames, then starts moving again with the same momentum it had before. It makes absolutely no physical sense but it feels fine because the effect is almost imperceptible. At a subconscious level that pause gives players a chance to register they’ve made contact, makes the impact feel weightier, and also gives the player and enemy animations a few frames to sync up before they start playing their reaction animations, which are often tied together.

Body mechanics

- Believable body movement boils down to: “where is the character’s weight now and where is it going?” It’s not easy, but it is simple.

- Movement looks better and more natural when things are leading and following. It’s partly physics (eg if you turn your head far enough it’ll start pulling your shoulder) and party because it helps lead the viewer’s eye and makes the motion feel cohesive / organic.

- Overlapping action is inherently beautiful. Even a simple tail settling feels strangely satisfying.

- Everything in the body is connected so forces in one area can often be felt as small motions elsewhere. As Richard Lico put it, “the spine is the echo chamber of the body.” For example, if you slam your hand down hard enough on a table then that force will ripple out and cause your feet to jiggle slightly. The one exception is that you generally don’t want to see pops and wobbles in your center of mass (often the hips) which should be slower to react, like the Titanic of the body.

- When you’re confused about how a body would react it helps to visualize body mechanics using simple spheres. You could imagine the relationship between the hips and chest as one ball balanced on top of another, so as the hips rise up then the chest will tend to roll forward or backward depending on how the chest is balanced over the hips.

- In real life, when the body is in motion the feet are almost always moving. Adding small foot movements like weight shifts, toe rolls, and squashing when the foot plants helps sell the overall physicality. The main thing is to always be doing SOMETHING with the feet.

- The more weight a foot is bearing, the less it’s going to slide around. If it’s rotating, it’ll be rotating around whatever point is bearing the most weight, as if it were pinned to the ground.

- Hands usually aren’t very noticeable in games. Having one or two great poses in an animation can be enough. They should look natural but they don’t have to animate much.

- Blinks need a one frame hold for audiences to notice them. Most of the movement comes from the upper lid though the bottom lid does move a little. Lids take longer to open than they do to close.

- If you’re trying to make unrealistic forces feel plausible, which is often the case in games where characters need to be able to do things like jump 10 feet into the air, it helps to start with real-world reference. If your initial body mechanics are believable it’s possible to push those quite a ways and still feel good. As you increase the forces, you just emphasize elements like the squash and stretch of the spine that are already there.

- In games, sometimes you have to secretly move characters around during gameplay, eg in combat you might want an enemy to be slightly closer so the player’s punch will connect in a more satisfying way. In those cases you’re often better off ignoring body mechanics for a few frames — sliding characters around is actually going to be less noticeable than having them take baby steps to cover the gap. Sometimes preserving the overall rhythm and flow is more important than accurate body mechanics.

- You have to consciously watch out for broken poses, where the body is bent in ways that feel uncomfortable or would actually be impossible. It’s easy to get so focused in one place (eg making the hips feel good) that you don’t notice problems you’re creating elsewhere, like ankles bending at painful angles. It’s especially true animating animals, where there are more legs to worry about and the body parts are less familiar. Your brain can only focus on so much at a time, so it helps to force yourself to do a separate pass to check that nothing’s broken.

- Don’t be afraid of broken poses at extreme moments, since that sort of thing actually happens in real life (eg a boxer’s face rippling under a heavy blow to the head) and can help convey just how powerful the forces are. It’s hard when you’re looking at a still frame of your character and their pose seems impossible, even if technically it’s not unrealistic.

A shot I animated for a class on animal emotions

Animating animals

- Most quadrupeds have a very similar pattern of motion for their gaits (walk, trot, gallop, etc). But the overall motion for each species looks quite different because of differences in their flexibility. Horses are very stiff, cats are supple, and dogs are somewhere in between.

- Quadrupeds are like rear-wheel-drive cars — the back legs generate most of the power and the front legs are primarily for steering.

- The biggest difference to keep in mind when animating quadrupeds is that their scapula isn’t attached to their skeleton, the way ours is. So when they walk or run their scapula absorbs a lot of the impact, causing it to move up and down while reducing the motion that would otherwise affect the chest and head.

- Different quadruped species have very distinctive upper silhouettes. Emphasizing that shape helps audiences identify the creature as a wolf, a dog, a fox, etc.

- Animals often keep their heads eerily stable, the way a chicken’s head freezes in space when you move its body around. This can make animations like running look fake, so sometimes it’s better to add a little rotation even if there’s none in the reference.

- Dogs can look at things out of the corner of their eyes but cats and most other animals generally turn their heads to face whatever they’re looking at.

- Hearing tends to be sharper than sight, so animals will react first with an ear flick and THEN look at a disturbance.

Posing

- You generally want to exaggerate all of your poses. It makes the action clearer and motions feel better. So much is happening and so quickly, it’s easy for motion to start feeling muddy. Pushing your poses gives you room to art direct and lead the eye where you want players to look.

- With good posing you should be able to pause at any frame and still have a clear sense of where the character is moving and what’s about to happen. If two characters are interacting, the forces should be readable even if you hide one of the characters; if they’re fighting it should be clear who’s in control / winning.

- In a walk / run cycle compressing the toes in a lot on the passing pose helps give you more contrast on the contact and liftoff poses when the feet spread out, creating a more organic feel through squash and stretch. Works for human and animal feet.

- Avoid flat poses (with everything in the same plane) or uniformity in spacing or rotation, eg feet facing in the same direction, or if the hands are spread open during a run, have the fingers splayed in a complex pattern with non-uniform spacing between fingers.

Workflow

- The longer you work on an animation the harder it becomes to make changes because the more keyframes you add, the more pieces have to be adjusted with every change. This creates a strange workflow, where early on it makes sense to work cleanly and focus on having sensible values and curves but there’s a point where the complexity grows so great that it makes sense to STOP caring about your keys and just look at your animation to diagnose what feels wrong. Working on new layers can help, but it’s often faster to blow away sections and redo them than it would be to fix the convoluted mess that’s there.

- Blocking out your poses with stepped keys forces you to focus on what’s actually important. There’s so much to keep track of when animating and almost all of it, before you get to polishing, looks awful. Working in stepped — which hides animation and only shows you the poses — is less distracting and gives you a chance to ONLY be looking at the parts of the animation that actually should look good at this point: your poses. As soon as you get out of stepped mode you’ll be drowning in new problems and after those are under control how good it feels will depend mostly on the quality of your core poses. It’s so tempting to stop posing and start animating, especially as a novice. I suspect it gets easier with experience, since you can look at stepped blocking and better imagine how it’ll feel once it’s animated, playing it out in your head.

- Animation takes EVERYBODY a long time. One of my instructors had been animating for 15 years and it still took him 4 solid days to do 3 seconds of combat. It’s a lot of work. You do get much faster over time, but since your eye for detail gets better too, reaching the point where you’ve made the animation as good as it can be still takes a similar amount of time, you just end up with better results.

- Working in the best coordinate space makes animating much easier. For example, if you want a sword to swing in a smooth arc it’s much easier to animate the tip of the sword moving in an arc and have that drive the hand than it is to try rotating the hand every frame to keep the sword’s tip where you want it to be.

- Switching coordinate spaces is faster than counter-animating and a lot more fun, once you’ve setup your tools and rig to support it. For example, posing arms is easier in IK while polishing is easier in FK, so Richard Lico just bakes all his data when the time comes and uses that to switch spaces. Instead of fixing wobbles indirectly in IK he can see all the offending keys in FK and just delete them.

- Baking locators lets you data-mine your existing motions to drive new ones, which is faster and more accurate than working from scratch. For example, to make a character’s ponytail bob while they run you cold attach a locator to the head and bake out the existing head motion, which you can then use to drive the ponytail. Once you’ve got keys on the ponytail it’s easy to move them around to do things like delay later sections to create more lead-and-follow, or make the rotations larger towards the tip so the ponytail whips around. Richard Lico’s tutorials on how to do all this are maddeningly simple and took me several viewings to understand. All of it boils down to tricks for taking the motion you’ve already created and using it to generate more. As Lico put it, “Or I could animate it [by hand]. That would be a nice way to never see my family again and that sounds like a fun way to spend my free time…”

- You animate very differently when you know exactly where you camera will be. There’s a lot of things you can cheat, like not animating the feet if you know they’re not going to be visible, or worrying less about the hand that’s farther away from camera. It also makes you more conscious of 2D issues like the amount of negative space in a character’s silhouette. In games we often don’t have the luxury of knowing exactly where the camera will be, since players might have moved it, but I think in a lot of cases we can make guesses with 90% accuracy so it probably makes sense to animate with a rough camera in mind.

- Periodically checking your animation from different camera angles helps you spot errors and places that feel lifeless. Issues that feel subtly wrong can jump out at you from other angles, making them much quicker to fix.

- One of the best ways to get better at recognizing what’s wrong in your own work is to look at the reels of other animators. You’ll see common mistakes repeated over and over and learn to spot them easier.

Tools + Tricks

- Motion trails are the single most useful tool for identifying what’s wrong in your animation. They instantly show you where your movements need to be smoother and also give you a nice visualization of the overall rhythm of a motion. Most of the polishing you do is fixing stuff that subjectively feels not-quite-right, so it’s comforting to have a tool like motion trails that show you in very concrete, actionable terms why something feels bad and how to fix it, eg “oh look, that foot is moving forward for 6 frames and then it suddenly moves back 1 frame, then keeps moving forward, let’s fix that.”

- The animBot plugin makes animating in Maya much easier, adding tons of useful features like super fast motion trails, tweening, reseting, copying or mirroring poses, scaling keys, quick selection sets, and lots more. The best part is that it makes all those new tools easy to discover at your own pace with great documentation ready when you want it.

- Keyframe Pro is the video player every animator needs. It’s a joy to use a tool that’s designed so well and so specifically to address your needs. When you’re animating it turns out there’s a lot of things you’d like to be able to do when scrubbing through a video. Like crop a section of the video and play it in a loop, or play it all backwards, or even upside down. Or draw notes on top of certain frames. Keyframe Pro does all that and then even lets you save that cropped video with all your notes to a new video file. It’s a beautiful piece of software that makes working with video a pleasure.

- Hiding body parts helps you focus on polishing one piece at a time. For example, when you’re trying to figure out what your hips should be doing it’s distracting to see the arms or head either not moving or moving strangely. By putting them on separate layers you can make them invisible and ignore them until you’re ready, like this:

- Sometimes brute forcing is easier because a “clever” solution is more trouble than it’s worth. One week I was animating a foot rolling off the ground which required some tedious frame-by-frame counter-animation and our instructor pointed out: “Having to do that is going to suck, but it’s only going to suck for three frames.”

- Sometimes a chain of sensible values can still produce a very odd-looking result. A character’s nose might move in a very jerky way, for example, because the rotations of her hips, chest, neck and head add up (and are out of step with each other) in such a way that there’s a wobble at the end of the chain. This requires you to “fix” the already perfectly good values so they don’t add up that way, which is counter-intuitive, or you could use Richard Lico’s space switching workflow to animate from the nose directly.

- Broken tangents help things feel snappier. They’re crucial for hard stops like when a foot lands during a run cycle, but they can also be useful any time you need a little extra, slightly theatrical emphasis to a motion.

Reference footage

- Almost every animation starts from video reference, either found footage or recordings you make of yourself acting it out. That’s true for students as well as professionals. It feels like cheating at first, as if every painting had to start from a photograph. But there’s so many subtle nuances in the way bodies move and convey emotion which you’d never think to add but can discover for free by studying reference.

- When studying video reference, focus first on what the hips are doing. Your key poses are likely to be at places where the center of mass (ie the hips) are changing direction.

- Finding reference animations and then editing them together into mood videos is a great way to explore how you want something to feel and also to communicate that to the rest of the team. They’re like the animation equivalent of concept art. Richard Oud gave a talk at GDC this year about his process of creating mood videos for Horizon: Zero Dawn.

- Video reference of actors (ie people pretending to do something) usually needs to be animated faster and with more powerful / painful impacts because even great actors will subconsciously protect themselves, which affects their performance. Real life reference is better but can be hard to find. Fail videos are a good source of how bodies react to intense, unforeseen circumstances.

- Video reference is even more important for animating creatures than humans, since we have a poorer intuition about how their bodies work and it’s harder for us to act out the motion. Unfortunately, finding good creature references is much harder and sometimes impossible. As a fallback you can use comparable animals, like studying chicken feet to see how dinosaurs might walk, which they did on Jurassic Park.

- When shooting video reference, having two perspectives (eg front and side) makes it much easier to figure out what the body is doing since body parts often get occluded at various points. If you can only shoot one take then a 3/4 perspective is good.

Fun facts

- Herbivores have huge digestive systems because their food is difficult to absorb, which gives them barrel chests and rigid spines, making them easy for people to ride. Carnivores, with their shorter digestive tract and much more flexible spines, would be almost impossible to ride.

- When people laugh unexpectedly their head moves forward sharply because their lungs expel a burst of air, causing their torso to bend.

My final assignment for a creature animation workshop

Conclusion

What I hope for most with any new experience is that it will help me see the world in a new way. As I’ve gotten older that’s been harder to find, but spending a year studying and practicing a skill I suck at has turned out to be a great way to rewire my brain. It’s been a year full of painful, useful failures that have forced me to notice all kinds of little details I was oblivious to before.

One of the biggest changes I’ve noticed is that when I see people walking on the street now I can’t help thinking about all the details that go into making a walk animation feel good. I flashback to the hundreds of hours I’ve spent at it and the mediocre results achieved. But these people are all walking around like it’s no big deal. Like it’s effortless.

Here’s the part that blows my mind. It’s not just that walking is an insanely intricate and graceful motion, or that every single person walks in their own distinctive way. It’s that — on top of all that — everyone walks differently depending on how they’re feeling right at that moment.

Surprise! It turns out we live in a world of unimaginable beauty and complexity. I don’t know why I keep forgetting that. At least now I can see it constantly walking around me.